Being a teenager is tough: juggling classes and extracurricular activities, navigating the high school social strata, scoring the best weekend plans with hot dates and the right party invites, figuring out college visits and summer jobs. But it gets even more challenging when your house is haunted by a pissed off ghost, your new friend might be a murderer (or an otherworldly monster), some anonymous creep is following you, and your classmates keep going missing or turning up dead.

From the late 1980s to the mid-1990s, there was an explosion of horror paperbacks marketed to teen readers—and particularly teen girls—by authors like R.L. Stine, Christopher Pike, Richie Tankersley Cusick, Caroline B. Cooney, Carol Ellis, Diane Hoh, Lael Littke, A. Bates, D.E. Athkins, and Sinclair Smith. Some of these novels followed the long-series form that was enormously popular in the larger teen fiction landscape at the time, like Stine’s iconic Fear Street series and Hoh’s Nightmare Hall, while others were standalone novels, with Scholastic’s Point Horror imprint as the gold standard.

Drawing on Gothic horror traditions, slasher film conventions, and over-the-top soap opera-style melodrama, these books were enormously popular among teen readers, who flocked to their local mall to hit up the B. Dalton or Waldenbooks for the latest scares, which ranged from the supernatural (vampires, werewolves, ghosts, and Lovecraftian-style horrors) to the all too real (mean girls, peer pressure, stalking, intimate partner violence, or loss of a loved one). Regardless of the nature of the specific threat, there was a preponderance of dark secrets, mistaken identity, and one “terrible accident” after another.

These books definitely weren’t literary masterpieces and often left readers with lingering, unanswered questions (like “who the heck is house hunting and thinks ‘gee, Fear Street! That sounds like a nice, not at all terrifying neighborhood. Call the moving company!’”). Some of the representations are more than a little problematic, particularly when it comes to gender representation, healthy relationships, and perceptions of mental illness. However, as a product of their unique cultural moment, they were effective horror bridges for teens who were too old for Stine’s Goosebumps and had outgrown Alvin Schwartz’s Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark series but weren’t quite ready for Stephen King or Clive Barker. At the intersection of three areas that are frequently disdained or derided—young adult literature, girl culture, and genre fiction—these books have never been considered worthy of significant consideration, largely dismissed as disposable and kitschy low-culture rubbish.

There’s a lot more here than meets the eye, however. In addition to drawing on traditional conventions of horror and the Gothic, these books are in direct conversation with the unique 1990s teen horror film moment, in which slick, commercialized, star vehicles supplanted their grittier, niche-ier predecessors. The changing landscape of technology and communication is a central focus of many of these novels as well, particularly early on in this cycle with A. Bates’s Party Line (1989), R. L. Stine’s Call Waiting (1994), and the creepy callers of Stine’s Babysitter series (1989-1995), among others. Several of them engage overtly with ‘90s Third Wave feminism, including its preoccupation with popular culture and representation (and some do so much more effectively than others). These teen horror books of the late ‘80s and early to mid-‘90s are a snapshot of a unique and quickly changing cultural moment, reflecting the fashions, passions, and anxieties of their characters and readers, as well as speaking more generally to the experience of adolescent girlhood.

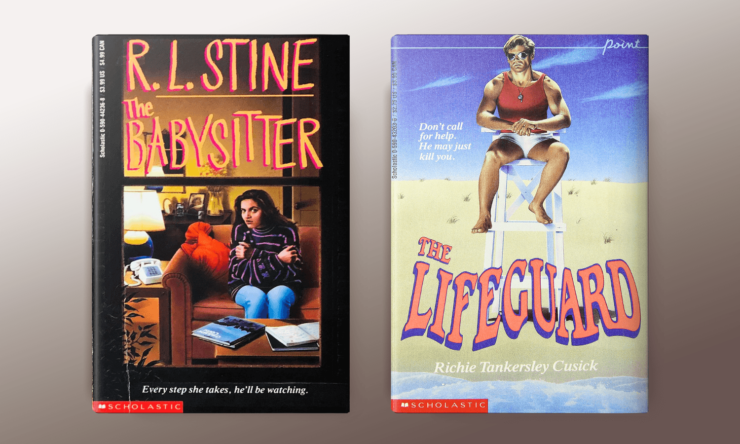

Point Horror began by publishing Blind Date in 1986 and Twisted in 1987, both by R.L. Stine. However, this teen horror trend didn’t really hit its stride and start to build an enthusiastic readership until the tail-end of the 1980s, and while Stine’s earlier contributions are the first, they are far from the most memorable. Two books that kicked this teen horror boom into high gear were Richie Tankersley Cusick’s The Lifeguard (1988) and R.L. Stine’s The Babysitter (1989). The Lifeguard’s cover art remains one of the most recognizable examples of this trend, with its menacing and stony-faced lifeguard, while Stine’s The Babysitter was so popular with readers that he continued Jenny’s story with three sequels. Both The Lifeguard and The Babysitter introduce trends of friendship, complicated family dynamics, and a realistically dangerous world upon which the teen horror novels to follow would build. While The Babysitter reminded readers that home is often where the horror is, The Lifeguard made it clear that nowhere is really safe. These two books firmly established the ‘90s teen horror trend, with themes and variations that reflected teens’ real world concerns (though hopefully with less murder) and would remain resonant for the next decade, making The Babysitter and The Lifeguard a great starting place for considering how these novels both build upon established horror traditions and create original narratives for their teen audience.

R.L Stine’s The Babysitter

Stine’s The Babysitter is an excellent example of telling an established story in a reimagined way for a new audience. Jenny Jeffers’ story of the terrorized babysitter is a familiar one, recounted in urban legends and Hollywood films, most notably When a Stranger Calls (1979, remade in 2006); even the protagonist’s double-J name is a direct echo of Stranger’s Jill Johnson. Additionally, the book’s tagline evokes The Police’s 1983 hit song “Every Step You Take,” with the ominous stalker-y vibe echoed in The Babysitter’s “Every step she takes, he’ll be watching.”

When the phone rings while Jenny is babysitting, instead of asking Jenny if she has checked on the children, the mysterious caller repeats variations of the same inquiry: “Hi, Babes … Are you all alone in that big house? Well, don’t worry. Company’s coming.” On the one hand, this is potentially a comforting subversion of the familiar “The Babysitter and the Man Upstairs” story, because if “company’s coming” that means the call can’t be coming from inside the house … just yet.

The cover art of the novel is in keeping with many earlier iterations of this particular narrative that put the listener/reader/viewer in a voyeuristic position as they tell the babysitter’s story, featuring an image of terrified Jenny as seen through a window. Stine’s The Babysitter, however, largely aligns the reader with Jenny Jeffers, making her experience and active negotiation of this terror the novel’s central focus, with Jenny a developed character rather than a cautionary campfire tale. Jenny’s central position to the narrative and the empathy Stine invites firmly situate her as a hero rather than a disposable victim, following in the tradition of the slasher film’s Final Girl to present the complex and subjective perspective of the endangered young woman, a narrative pattern that dominated successive teen horror novels and invited the self-identification of teen girl readers.

Throughout The Babysitter the reader is invited to empathize with Jenny as she works her way through the list of suspects, debates whether or not to call the police or tell the parents for whom she is babysitting about the phone calls, and has complicated moments of both cowardice and bravery, trembling at every bump in the night but also venturing into the darkened backyard to investigate a strange noise and confront a prowler. Readers also get to know Jenny better than the usual sacrificial babysitter, as her experience extends well beyond a single night of horror (as in earlier versions) as she returns to the Hagens’ house for her babysitting gig over the course of several weeks.

Jenny’s isolation is overt: the neighborhood is secluded, she has to take a bus to get there in the evenings (and the bus is almost always late), and at the end of the night, she is driven home by the increasingly odd Mr. Hagen, who zones out, talks cryptically about his dead child, and lapses into long and unsettling bouts of silence. As a result, Jenny often finds herself in a relatively powerless position, with few options. She endures variations of tension and fear, rather than being able to look forward to a sense of safety with the return of the adults or a clear end to the terror. When she is alone at the Hagens’ house, she lives in fear of the next phone call and knows that if anything happens, no one is close enough to save her, even if she is able to call for help (which is far from a sure thing), and when the Hagens come home, Jenny still has to endure the inescapable and uncomfortable car ride with Mr. Hagen. In both of these cases, Jenny’s fear is diffuse and impossible to pin down—there’s the sense that something might happen, that something could be wrong—but with no clear threat to which she can respond, Jenny often finds herself mired in a state of uncertainty, doubting her own intuition and facing this fear alone.

Jenny’s agency is also limited by the fact that she and her mother are struggling to make ends meet, a pragmatic reality that keeps Jenny going back to the Hagens’ house long after she is comfortable or feels safe doing so. While issues of class are rarely overtly discussed in ‘90s teen horror, many readers could likely identify with Jenny’s situation as they worked to earn their own spending money, save for college, or help support their families. As a result of Jenny and her mother’s financial situation, the stakes of Jenny’s babysitting job are pretty high, as she reminds herself that she needs this money to help her mom pay the bills and buy Christmas presents for friends and family. Being creeped out isn’t a good enough reason to walk away from this well-paying job, particularly when Jenny can’t quite put her finger on or explain to others exactly why she feels so uncomfortable and afraid. While teen viewers might watch the latest horror film, incredulously asking “why would you go in that dark room?”, for Jenny the answer is pretty straightforward: she and her mom need groceries, they need to pay the electric bill, and there’s no one else to help. It’s not that Jenny has no choice, but given her family’s needs and financial situation, her choices are pretty limited.

Additionally, every single guy Jenny interacts with in The Babysitter is a creep to one degree or another, which leaves her trying to figure out which of them is the most likely to be creepy and dangerous. This fear is pervasive, even beyond the context of the creepy phone calls and attempted murder, as Jenny realizes that the world at large is not a safe place and she can’t trust anyone. Jenny feels particularly vulnerable when she’s babysitting at the Hagens’ house, but she also has moments of fear at the mall, the local pizza place, and even within her own home, as Stine creates–or more accurately, reflects–a world in which the teenage girl is never truly safe. The threatening calls she receives at the Hagens’ house are an extreme example of this, but she is also followed by an anonymous man on the street and has to deal with Chuck’s anger when she turns him down for a date, adding a pervasive sense of vulnerability and fear to her everyday life beyond babysitting. Mr. Hagen ends up being the big winner in the creep lottery: he’s the one making the calls, his behavior is erratic and unpredictable, and his worry for his son’s well-being often borders on hysteria. In the end, he tries to kill Jenny, projecting his blame and vengeance on her as a proxy for the babysitter he holds responsible for his young daughter’s death, viewing these young women as interchangeable and worthy of his murderous retribution.

But right up until the point when he kidnaps Jenny and tries to push her off a cliff, Mr. Hagen is actually on pretty even creep-o-meter ground with both weird neighbor Mr. Willers and Jenny’s potential love interest Chuck. Willers skulks around the Hagens’ dark yard and chases Jenny down the street. Chuck scares Jenny by jumping up outside the window in a Halloween mask and ignores her when she tells him she doesn’t want him to come to the Hagens’ house while she’s babysitting, repeatedly telling her he was “just joking” and dismissing her anger and fear. (Chuck also “did some pretty gross things with a bunch of bananas he found on their kitchen table,” but that’s neither here nor there). When Jenny is terrified, she is told she is imagining things, that she’s overreacting, and that she misunderstood what these men meant. As a result, she talks herself into ignoring the alarm bells of her intuition, as she struggles to identify which of her fears are “legitimate.” Like too many of the girls and young women who read these novels, Jenny is dismissed and doubts herself, a response which puts her in further danger.

Jenny keeps making out with Chuck even when she thinks he might be the one terrorizing her, not wanting him to think she’s some uptight prude and thrilled that there’s a guy who’s interested in her, despite her many reservations about him. Mr. Willers is an undercover cop who was watching the Hagens’ house and trying to warn Jenny, but ends up using Jenny as unwitting bait in a ruse that ends with her nearly being murdered and Mr. Hagen falling to his death. When she calls him out on this massive error in judgment, his grumpy response is for her to “Give me a break … This didn’t turn out the way I’d hoped. Believe me.” Willers (real name: Lieutenant Ferris) doesn’t apologize and boyfriend Chuck doesn’t learn to stop kidding around or respect Jenny’s boundaries, but at least neither of them actively tried to murder her, which presumably makes them good(ish) guys.

In the end, the immediate danger posed by Mr. Hagen has been neutralized and Jenny has temporarily sworn off babysitting, but she’s still dating Chuck (who can’t manage to quit cracking jokes even as Jenny struggles to cope with the immediate aftermath of being almost murdered) and given her family’s financial position, she’ll likely find herself taking a job she’s not really comfortable with or that puts her in another potentially dangerous situation in the not-so-distant future.

(Over the course of three sequels, things don’t get better for Jenny, with hallucinations, questionable boyfriends, a problematically-presented Psycho-style case of dissociation, ghosts, and more babysitting than seems wise for someone who was nearly murdered while babysitting).

Richie Tankersley Cusick’s The Lifeguard

While The Lifeguard doesn’t build on established urban legends or popular culture narratives as overtly as The Babysitter, there are some notable similarities between the two books.

Kelsey Tanner is spending part of her summer vacation on Beverly Island with her mom, her mom’s boyfriend Eric, and Eric’s kids … except for his daughter Beth, who goes missing the day before Kelsey and her mom arrive on the island. Like The Babysitter’s Jenny, Kelsey is isolated, with no car and no way off the island other than the twice-daily ferry to the mainland. She becomes even more isolated when Eric has a heart attack and Kelsey’s mother stays with him at the hospital on the mainland, leaving the teens to fend for themselves (a frequent state in both teen horror novels and slasher films, as parents, police, and other authority figures are often either absent altogether, ineffectual, or abusive).

Also like Jenny, Kelsey is surrounded by a range of objectionable and creepy dudes, again reflecting a world in which young women are never really safe. Eric’s oldest son Neale is antagonistic and rude, while another one of the lifeguards, Skip, is wealthy, entitled, and vacillates unpredictably between charm and condescension, including a rant about “crazy, lamebrain female[s]” who get freaked out by finding a dead body. Neale has some shadowy history that includes a stay in a mental institution and Skip waxes on in eroticized fashion about how much he enjoys stalking animals and the thrill of the hunt. A local eccentric with a drinking problem and an eye-patch colloquially named Old Isaac is suitably creepy and repeatedly tells Kelsey that if she isn’t careful, she’ll end up dead too. Overt threat of violence or friendly—if creepily-delivered—advice? Only time and attempted murder will tell.

However, these three are all red herrings for the real serial-killing lifeguard: Eric’s younger son Justin, who is simultaneously Kelsey’s potential future stepbrother and summer love interest (an unsettling Venn diagram overlap to say the least). But Justin is friendly and shy and “his eyes were big and brown and gentle,” so Kelsey is certain that he could never be the murderer. Important teen horror life lesson: you can’t trust the creeps (obviously) but you also can’t trust your almost stepbrother/kind of boyfriend/nice guy. No one is above suspicion.

The Lifeguard features a protagonist who has already survived some significant trauma, with that experience coloring how she responds to these new horrors. This builds on the slasher film’s Final Girl trope, particularly in the Final Girl’s reappearance in sequels and ongoing series, where she has been fundamentally changed by what she has endured. In this case, Kelsey has a recurring nightmare of the death of her father, who drowned after saving her following a boating accident. The island, the beach, people constantly swimming, and a murderous lifeguard who keeps drowning people (unsurprisingly) exacerbate Kelsey’s fear and trauma, which results in her doubting her own subjective experiences and sense of the immediate danger.

The Babysitter and The Lifeguard aren’t the most feminist of these ‘90s teen horror novels: both Jenny and Kelsey repeatedly turn to men to protect to them, even when they know that those men are potentially dangerous. Both Jenny and Kelsey doubt themselves and their own perceptions, willing to believe that they’re overreacting or have somehow misunderstood what’s right in front of them. What these young women discover, however, is that trusting their intuition is key to their survival, both within these particular situations and the world at large. If something doesn’t feel right or if they feel unsafe, these young women learn to trust that sense, even when they can’t pinpoint or explain to others why they feel uneasy. These are imperfect awakenings, with Jenny and Kelsey frequently returning to self-doubt, but the validation of these fears is essential, both for the characters and the readers.

The Lifeguard also introduces a trend that is common in these teen horror novels, in its revelation that characters presumed dead aren’t really dead at all. When Beth is found in the novel’s final pages, she is near death, but pulls through. Kelsey’s new friend Donna survives being pushed off a cliff (when the not so detail-oriented murderer thinks Donna is Kelsey because she’s wearing the other girl’s jacket). Kelsey survives her ordeal, with her perseverance and their shared trauma miraculously turning Neale into a sensitive guy who wants to hold Kelsey’s hand and talk about his feelings (and like Justin, is her potential future stepbrother). This pulls the punch of much of the novel’s violence against women and the life-threatening dangers they encounter, allowing readers to indulge in a cautionary tale where all (mostly) works out well, as long as we don’t think too long or hard about the nameless, faceless victims that came before these young women.

The cover of Cusick’s The Lifeguard is one of the most iconic of the Point Horror novels, featuring a muscled, blonde, and unsmiling lifeguard sitting atop a lifeguard station, looking over the water and directly out toward the reader. This eponymous lifeguard is ominous and unfeeling, radiating a clear aura of danger. This unsettling image, coupled with the tagline “Don’t call for help. He may just kill you” underscores the reality that in these teen horror novels, it’s best to trust no one, whether in suburban babysitting or on an island vacation. That’s certainly the best strategy for staying alive.

Alissa Burger is an associate professor at Culver-Stockton College in Canton, Missouri. She writes about horror, queer representation in literature and popular culture, graphic novels, and Stephen King. She loves yoga, cats, and cheese.